Illustration: Pushart

Nichole Selan recalls lying in bed at the age of six or seven, wondering why she was a boy when she was supposed to be a girl. Even when she understood the word transgender, she rejected the idea that it described her. “I grew up in the ’80s and ’90s,” says the Lawrenceville resident, now 42, “and trans people were just a joke then. When I saw trans people, I thought, Well, that’s not me because I’m not some kind of weirdo.” When she was in her 30s, she watched TLC’s I Am Jazz, a reality show about a young, transgender woman that premiered in 2015, and thought, Man, I wish I was transgender so I could transition, too.

Eventually, she did transition—five years ago, at the age of 37. But, like many other transgender people of her generation, it took time to come to peace with the idea of doing so. What she shares with trans people of all ages is the sense, often overwhelming, that she’d been born in the wrong body. She’s grateful that she lives at a time when medicine can bring her physical gender into sync with her psychological gender, via gender-affirming care.

[RELATED: New Jersey’s Top Doctors]

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), gender-affirming care “can include any single [intervention] or combination of a number of social, psychological, behavioral or medical (including hormonal treatment or surgery) interventions designed to support and affirm an individual’s gender identity.”

Those seeking such care may be transgender (meaning they feel that their body is at odds with their true gender) or nonbinary (they perceive their gender as neither male nor female). They may have gender dysphoria, a sense of distress stemming from a mismatch between one’s physical and psychological genders, or gender incongruence, that same sense without feelings of distress. In 2019, the WHO announced that it would no longer classify either condition as a mental disorder, reflecting the 2013 decision by the American Psychiatric Association (APA) to replace the diagnosis “gender identity disorder” with “gender dysphoria,” in the hope that the new wording would help transgender individuals avoid stigma and ensure that they receive clinical care.

That hope seems to be fading for many transgender Americans, as a burgeoning movement to restrict gender-affirming care gains steam.

MOVING FORWARD, PUSHING BACK

In the last decade, the field of gender-affirming care has grown exponentially, particularly since 2016, when what was then called gender-reassignment surgery was no longer deemed experimental under the Affordable Care Act, and thus could be covered by Medicare and Medicaid, as well as most private insurance plans.

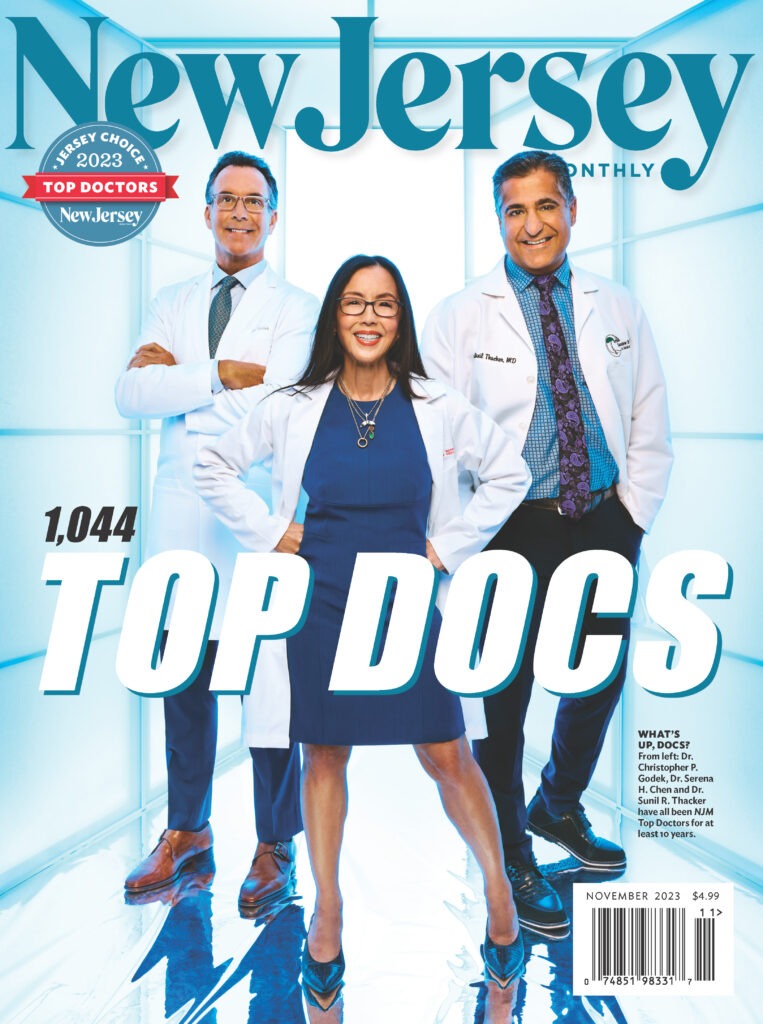

Buy our November 2023 issue here. Cover photo: Brad Trent

“From that, you really had the floodgates open in terms of the number of patients seeking care,” says Dr. Jonathan Keith, a Livingston-based plastic surgeon who specializes in gender-affirming surgery. As he explains it, “It’s not that they were newly identifying as transgender or gender-noncomforming. It was just that their insurance now afforded them access to some surgical procedures, hormone therapy, mental health services, etc.”

Because the number of surgeons trained in gender-affirming surgery hasn’t kept pace with demand, many, including Keith, have waiting lists of between one and four years for surgical procedures.

But, while Keith’s practice and others in the Garden State are booming, that’s not true in many other states, where gender-affirming care has been banned or severely limited, especially for transgender youth. As of this writing, 22 states have banned or restricted gender-affirming care for minors, and 10 others are considering bans. In addition, nine states don’t allow Medicaid coverage of gender-affirming hormone treatment, and 22 disallow Medicaid coverage of gender-affirming surgery, effectively making these treatments unavailable to many lower-income residents.

The pushback has prompted some states to legally affirm the right to such care. In April, Governor Phil Murphy signed an executive order declaring New Jersey a safe haven for transgender people, prohibiting the extradition of anyone here to another state for providing, receiving, or facilitating gender-affirming care. LGBTQ organizations widely lauded the move. “It means everything,” says Damien Lopez, project manager at Garden State Equality, New Jersey’s leading LGBTQ-rights organization, and himself a transgender man.

A GLOSSARY OF CARE

There’s a misapprehension that gender-affirming care—for adults, at least—always involves surgery. In fact, such care “is quite a varied landscape,” says Dr. Petros Levounis, chair of the Department of Psychiatry at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School, president of the APA, and a provider of psychiatric care at Rutgers Center for Transgender Health. He notes that “there are many options: medical procedures, surgical procedures, no procedures at all.” Gender-affirming care might be limited to hormone treatments or include one or a variety of surgical procedures. Some transgender people don’t opt for any sort of medical treatment, though they may undergo psychotherapy to deal with the anxiety and/or depression that can often accompany gender dysphoria.

[RELATED: New Jersey’s Focus on Compassionate Care]

Transgender hormone therapy (also called cross-sex hormone therapy or gender-affirming hormone therapy): For many who are transitioning, hormone therapy is the first medical step. Therapy consists of the administration of either the male sex hormone testosterone or the female sex hormone estrogen to bring about physical changes that enhance secondary sex characteristics. Among other effects, testosterone causes the growth of facial and body hair, a lowering of the voice, and redistribution of body fat; estrogen causes the growth of breast tissue, skin softening, and body-fat redistribution. To maintain most of these effects, therapy must be lifelong.

Gender-affirming surgery (also known as gender-confirmation surgery): Between 2016 and 2019, likely attributable to the expansion of insurance coverage, the number of gender-affirming surgeries performed annually in the United States tripled, from 4,552 to 13,011. That number dipped slightly in 2020, the first full year of the pandemic, to 12,818.

Surgeries commonly referred to as top (breast) and bottom (genital) are the most likely to be covered by insurance, though currently, less than half of transgender individuals opt for surgery of any kind; the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) estimates the number at between 20 and 40 percent of the trans population.

For those transitioning to male, bottom surgery options include phalloplasty, the construction of a penis, and metoidioplasty, the construction of a penis specifically using tissue from the clitoris—procedures undergone by roughly 3 and 2 percent of the trans population, respectively. Less common is scrotoplasty, the construction of scrotum and testicles. Fourteen percent of trans men also choose to undergo a hysterectomy, the removal of the uterus and cervix; some opt for a salpingo-oophorectomy, removal of the fallopian tubes and ovaries. Other surgeries, often not covered by insurance, include body contouring and pectoral implants.

Between 5 and 13 percent of trans women undergo bottom surgery, which can include removal of the testicles, removal of the testicles and penis, and vaginoplasty, the construction of a vagina from existing genital tissue.

Trans women may also choose facial and body-contouring procedures designed to feminize the appearance, tracheal shave to reduce the Adam’s apple, transgender hair transplant, voice feminization surgery, and electrolysis of facial and body hair.

Puberty blockers: These medicines block the production of sex hormones, including estrogen and testosterone, to halt the process of puberty. They can be given at any time during puberty, but the earlier they’re started, the less likely the patient is to undergo irreversible pubertal changes, like the growth of facial hair in boys and breast growth in girls. They are considered reversible interventions, but may come with side effects.

Putting a child on puberty blockers “is like hitting the pause button—if you remove them, puberty proceeds as it otherwise would have,” says Dr. Sari Bentsianov, an adolescent medicine specialist with Rutgers Transgender Health Services. However, she notes, side effects are still possible, most notably, a negative effect on bone density.

If patients want to continue to transition, they’ll be taken off puberty blockers and prescribed cross-sex hormones, which can be started as early as 13. The decision to do so requires parental consent and assent from the patient—a statement saying that they want to go ahead with the treatment and understand its risks and benefits. Many practices, including Bentsianov’s, require the opinion of a mental health provider.

Hormone therapy is considered a partially reversible intervention, meaning that, while some effects, such as softening of the skin and a pause in menstruation, can be reversed by stopping the therapy, others, like breast development and voice-lowering, are permanent.

Those irreversible effects are often cited as a reason not to treat adolescents with gender dysphoria, but instead wait until they are at least 18 years old.

Psychotherapy: Though psychotherapy is not a legal prerequisite for those looking to transition medically, patients often seek it out. “Transitions are almost always anxiety provoking,” says Levounis, “so we’re there to discuss and resolve this ambivalence and support the person, no matter what they decide to do with their lives.”

In 2022, the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH), a professional organization devoted to the treatment of gender dysphoria, issued revised guidelines for gender-affirming care, removing the recommendation that adults receive psychotherapy before gender-affirming medical interventions, but suggesting that minors undergo counseling prior to the prescription of puberty blockers or hormones. The guidelines also state that, in minors, any co-occurring depression or anxiety should be reasonably well controlled before treatment. The WPATH guidelines aren’t legal requisites, but many clinicians follow them.

MINORS AND TREATMENT

According to a 2023 national survey of young people regarding their mental health by the Trevor Project, a nonprofit focused on preventing suicide in LGBTQ youth, 20 percent of transgender and nonbinary young people (between the ages of 13 and 24) have attempted suicide, versus 10 percent of cisgender young people (those who identify with the gender they were assigned at birth); 50 percent have considered suicide in the past year, versus 33 percent of cisgender young people; nearly 75 percent experienced symptoms of anxiety and more than 60 percent experienced symptoms of depression during the past year, compared to 60 and 40 percent respectively, of their cisgender peers. “Kids who are not validated in their identity, whether it’s social or medical intervention and validation, can have much higher rates of depression and anxiety and suicidality,” says Bentsianov, adding, “For some patients, lack of intervention can significantly worsen their dysphoria and emotional distress.”

[RELATED: More LGBTQ-Friendly Health Care Facilities Emerge in NJ]

As for surgery, Keith says that neither top nor bottom surgery for minors is outlawed in New Jersey and are up to the discretion of surgeons. He, for instance, will perform masculinizing top surgery in some cases for patients under 18 with parental consent if those patients have undergone years of counseling, in accordance with WPATH guidelines. He doesn’t know of any doctors in New Jersey who perform bottom surgery for minors.

Some who argue against offering gender-affirming care to minors claim gender dysphoria and incongruence are fads picked up from social media; as evidence, they point to the large jump in the percentage of young people declaring themselves transgender.

It’s true that that number has risen dramatically, nearly doubling from .7 percent (or 150,000 adolescents) in 2017 to roughly 1.3 percent (or 300,000 adolescents) in 2020. But proponents of gender-affirming care say the increase may well be a reflection of the cultural shift, at least until recently, toward the acceptance of trans people.

DECIDING TO DETRANSITION

A common argument against medical transitioning at any age is that a large number of people regret the decision to undergo surgery. While there are transgender individuals who choose to surgically detransition, the available statistics don’t tell a story of widespread regret.

A 2021 review of 27 studies, published in the journal Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery—Global Open, found that only one percent of those undergoing any kind of gender-affirming surgery regretted it. External factors like social stigma appear to account for, or contribute to, the majority of decisions to detransition. Another 2021 survey published in LGBT Health found that more than 82 percent of those who detransitioned reported at least one external driver, including family and/or social disapproval.

HAPPINESS AND FEAR

According to the experts New Jersey Monthly spoke with, it appears that most people who transition are deeply satisfied with the decision. “For the most part,” says Levounis, “a significant happiness comes along with aligning the person’s gender with their physical appearance.”

For Jadis Montijo, a resident of Long Branch who underwent top surgery five years ago, transitioning not only helped vanquish his sense of gender incongruence, but also increased his self-confidence—“the confidence I lacked being in a body that didn’t feel like it fit me. I came into myself as a person, as an entrepreneur.” Post-transition, he founded a scar-treatment company, Motivo Scar Care.

Lately, though, for many trans people and providers of gender-affirming care in the Garden State, that excitement has been tempered with anxiety, thanks to efforts in many other states to restrict or criminalize aspects of gender-affirming care. “All of us in the field worry about any of it encroaching here,” says Dr. Diana Finkel, a community provider in the greater Newark area who treats many trans patients and works with Rutgers Transgender Health Service.

In one sense, it already has. Keith has started to encounter what he calls “roadblocks, barriers, and hoops to jump through” from some insurers, who, he says, have become increasingly adversarial about compensating patients for gender-affirming surgery.

And while the current administration clearly has the backs of gender-affirming providers and patients, not everyone in the state is as supportive. Last year, for instance, State Senator Edward Durr (R-Logan Township) introduced a bill called the Child Protection and Anti-Mutilation Act that would criminalize, among other things, puberty blockers.

Nevertheless, New Jersey remains a beacon for trans people seeking gender-affirming care. Keith notes that in his clinic, he’s seeing what he describes as “an influx of patients not just from New York and New Jersey, but from all over the country.”

“It’s a very scary situation,” says Lopez, “when we don’t find the medication we need, when we encounter obstacles to affirming our identity and maintaining our safety.” On the other hand, he says he feels very safe here in New Jersey: “The governor’s executive order reminds me that we’re moving into a very progressive and compassionate future and extending a hand to those outside the state to remind them that we see them.” For now, though, that compassionate future remains more of a hope than a certainty.

Leslie Garisto Pfaff is a frequent contributor to New Jersey Monthly.

No one knows New Jersey like we do. Sign up for one of our free newsletters here. Want a print magazine mailed to you? Purchase an issue from our online store.